Interview with Remote Artist-in-Residence Karin Bolender/R.A.W.

By Noelle Herceg

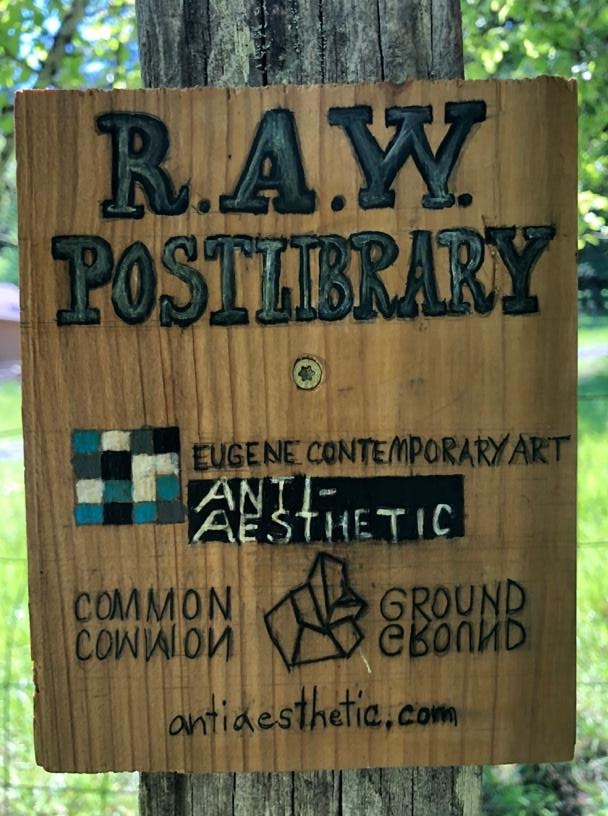

On Friday, May 8th, I had the pleasure of visiting the Rural Alchemy Workshop (R.A.W.) in Philomath and spoke with artist and founder Karin Bolender Hart (aka K-Haw Hart), current remote artist-in-residence for Common Ground at Eugene Contemporary Art’s ANTI-AESTHETIC.

Karin, or K-Haw, is an artist-researcher, writer, and teacher. She founded the Rural Alchemy Workshop (R.A.W.) on a small farm in rural Georgia in 2008, and since then she has maintained a rural-based ecological art practice under the auspices of the R.A.W. She teaches art history, and has an MFA in Interdisciplinary Art from Goddard College and a PhD in Environmental Humanities from the University of New South Wales in Australia.

The material below pulls from key moments in our conversation in the R.A.W. ass pasture, sitting six feet apart next to a temporary pond, with 7-year-old Rolly playing by the pond edge a few feet away, four asses not too much further, and thousands of other creatures and ecologies in the shared space.

***

Noelle Herceg: How did your relationship with Aliass begin?

K-Haw: The “R.A.W. Assmilk Soap” essay [in the Multispecies Salon collection] doesn’t really cover her back story, but it goes into my discovery of the spotted ass, and was the space to expand on “pre-ass” history. It was ultimately about language: the space between inter-species relationships, specifically with equines.

I grew up in Rhode Island and my mother had always wanted horses growing up. She was a military kid, and always traveling, but was able to visit the ancestral farm in Ohio, and dreamed of having her own horse. And she kind of raised me to love horses, which I did.

H: Oh, I was definitely a horse girl.

K: Did you love them? Did you get into them over time?

H: I had a friend who rode horses, and sometimes I would get to groom them with her. I was actually a military kid too, and while living in Germany we lived close to a barn that we walked to often to see and feed the farmer’s three horses (Mona, Monique, and Angelique). So there was some engagement, but it was more of a oh I just love them, kind of dreaming about them.

K: They’re actually really magical. That’s another thing about my relationship with Aliass: it continues to nourish the project and everything, but she is genuinely so magical to me. She might as well be a unicorn. When people meet her, the magic isn’t necessarily immediately evident. But it’s there.

Speaking of magic, we know an actual unicorn. The group Kultivator in Sweden has a horse, Tussan who has a teeny-tiny horn growing out her ear. We are doing a multi-species families project with Kultivator that was supposed to be this summer, but is postponed until next year.

R: And there’s a horse named Burberry!

K: Burberry, yes. She’s amazing. Burberry, is collaborating with a group of dancers in Stockholm right now, over Zoom! So Burberry’s been Zooming! It’s pretty incredible. She is a tense horse, who has a forcefield around her, and after a meditation session the group did, Burberry went down to the corner of the barn, laid down, and went to sleep. Knowing her, it was incredible. Something happened there for sure.

H: What is your relationship like with the animals here with you now?

K: We mostly just care for them, and caring for them is completely integrated into everything we do. In both good and bad ways: it means a lot for them to be here, but can also be a constraint when we need to travel, and financially to live in a place that has room for them. But I couldn’t imagine living without it. Their presence is so important.

We plan to do more with them when we have more time. Rolly has actually ridden Aliass in the local parade three times.

H: Wow! What was that like?

R: Last time, we died her mane rainbow!

K: It was the official re-launch of the Ass In Space Society of America (aka A.S.S.A). ASSA was invented years ago with a friend when Passenger was a baby. (There’s a frog!) The motto, which I need to make more catchy, is “we have to get our asses off this planet, but until we figure out how to do that, we need to take the best care of this planet as we can.” That was also kind of an intervention, because Philomath has an interesting set of political and cultural tensions…

(R: Look, deer!)

K: There’s another organization called E.A.R.T.H. (Environmental Art, Research, Theory, and Happenings) Lab, run by Beth Stevens and Annie Sprinkle, phenomenally wonderful environmental artists with long histories of contributing to a different way of thinking bout environmental art. I ended up reaching out to them in 2018 and doing a Secretome Project (they were planning a celebration of soil called the SeedBed Soil Symposium, named after a performance by Vito Acconci). It was two days at the Agro-Ecology Farm in Santa Cruz, and we were able to use the grounds of the farm in creative ways. The Secretome workshops adapted to the farm space: a question of the Secretome being “what is the treasure that you’re searching for?” It’s not meant to be defined, but rather, explored. We managed to find someone to bring a spotted ass to the farm (Benito), where we all convened in the parking lot and it was wonderful to have his presence there, for everyone able to have an encounter with him after experiencing the Secretome [which is inspired by a “treasure map” made from a culture of Aliass’s tongue].

H: Maybe this can be a segue into your work with the PostLibrary project. I’m curious, why here? In this space that is yours, is it meant to be a public encounter with people of Philomath, or more for you?

K: I should tell you first about how we are opening it. I like to think of it as being open, while opening at the same time. The PostLibrary is very much about time, and it’s also an opportunity to realize its other connections as a conceptual project. I’m thinking of having a series of “posts” for the ECA Common Ground website, that are on some of its external influences, the “post—”s that connect to it: post-modern philosophy, posthuman theory, postporn, and the postwestern [to name a few]. All of this work is about trying to find different ways to make spaces for stories that are co-composed with others. So, the PostLibrary is a space specifically for that, which is so exciting because I’ve had that as a guiding principle in my work for years and years, and this came together so well with the Common Ground programming with Agnese.

I’ve struggled with this idea of the book as an authoritative container, and I mean really struggled with it… but the PostLibrary becomes a place of exchange, makes a space for active inquiry, and immediate exchanges. Just this week, we did a collaboration with Jill Baker and her son (ooo, is that an egg?) and I realized the Secretome is really an appropriate way to open the PostLibrary. It is a form, that makes space for these “untold” stories: a portal into what else can happen in that space.

H: Why the book hanging? Why that book?

K: So that is part of a larger [postwestern] pulping project; there are other pulpings going on elsewhere around here, each one unique. The pulping process does involve reading them, which was Rolly’s suggestion, and I think it’s right; they need to be metabolized in significant ways. For this book, The Day of the Hangman, I noticed I just had a lot of books by that author [gathered somewhat randomly and in bulk from the Lions Club Book Sale at the Rodeo Grounds last fall], and after reading this one author bio I felt we have to pulp this book right now—which is the first “public” pulping.

H: This week I read some Derrida, and I better understand your take on “nature,” being a word that shouldn’t be taken at surface value. And then on Wednesday, I listened to an episode of the podcast “On Being” with Krista Tippett, with Ocean Vuong, in which Voung talks about the violence of our language… There’s this one quote that stuck with me I wanted to share. “We tell our children that the future is in their hands, but it’s really in their mouths.” Did you want to touch on language specifically, and how this moment in art and ecology could be a time of reflection in how substantial language is to make or guide those relationships?

K: We are always searching for ways to weave in and out of language. Language is a source of a lot of woe, grief, and limitation. But at the same time it is also a means of moving into deeper understanding, and a means of making beauty. If we interact with it creatively and critically and we are careful and attentive in all the ways we need to be to what language is doing, which are infinite, it is a means out of its own problems, or at least a means to reckon with them. And as a parent, I recognize, everything that we say, matters. It makes our lives what they are; it makes our bodies what they are.

I’m really appreciative to have this [remote residency] opportunity, at this particular time, because the PostLibrary coalesces a lot of different threads and questions and ways of thinking—especially with the role of the Western being so much about claiming territory. I’m trying to begin thinking about decolonizing modes of thought and language and “story grid.”

I have previously, inadvertently been inspired by Deleuze, my field is so influenced by Deleuzian thought. Now I am actually looking at the original sources of Deleuze and Guattari, and understanding how Deleuzian philosophy and ecology go so well together. There is a dissolution of categories, boundaries, and hierarchies, and the idea of transcendence that allows us to think that nature is one thing and humans are another thing… All of that Deleuzian thought allows us makes so much sense with ecology because I really feel like that [dissolution and intermingling] is what is happening, genuinely going on. To think that there is the discrete human body—separate from the environment that is not being affected by or affecting anything in exactly the way we can name and know, is absurd.

H: Why specifically art and ecology as an importance, right now?

K: Historically, there has been somewhat of a parallel process in post-modern thinking and philosophy and art, all of those things evolving together. The late 20th/21st century has shown that art has the capacity to be political and speak to larger issues. Not just a capacity, but to some degree, a responsibility to speak to bigger concerns. Contemporary art in particular has that thrust. And then the history of environmental art as such parallels the environmental political movements: so artists feel somewhat a responsibility to address ecology and of course, we have a lot of concerns happening now, that we didn’t have even forty years ago in the same way. They were threats, but they weren’t as existential or encompassing as the threats we are trying to reckon with now. I don’t think art can even fully reckon with the hugeness of climate change; I don’t think any one of us can wrap our minds around it, or even collectively. But I think the expansion of media and the conceptual apparatuses that contemporary art allow us to go as far as we can go, in thinking ecologically, with the sense still that there’s still so much further to go—as we get more of a concept that ecology isn’t just grass. Do you feel like that’s what it is going on with art and ecology?

H: It’s so big, and you said it’s expanding so wide that we kind of have to go deeper instead of further. Going back to the small relationships, to feel like we can make a bigger difference.

K: Yeah, and to not be paralyzed by the hugeness of something like climate…

This right here is infinite. Rolly had an assignment this week to take a hoola-hoop and examine everything encompassed in that space, and even that is infinite. When you start thinking of all the ways you can dig into the history of the species… how did this particular plant come about here? When you start thinking at that level of the vast amount of constant change and shifting and movement and histories of every single living thing, it blows your mind. And the humility that instills, when you realize just how little we know.

Overall, the PostLibrary is something that will go on indefinitely, and will continue to evolve as a space. And this has been a wonderful opportunity for it to actually take shape and start to work as an exchange. It feels like such a gift to, to have these experiences (you, Jill and Fox) with new people in the conditions that we’re in. How do we begin to process that we’re in this Pandemic situation, where everything has changed and time moves differently?

***

There was a sort of magic sitting outdoors with K-Haw and every other participant to our conversation, including the deer, frogs, birds, trees, and bees. After our conversation I was fortunate to meet some of them, following the R.A.W. Secretome (not)map created by the culture from Aliass’s tongue (another photo of which sits inside the PostLibrary). My own experience of the Secretome led me through a journey of being guided in movement by the small sounds around me, beginning with a duet with a wasp, and concluding laying down beside the temporary body of water we spoke next to. The PostLibrary brought warm, meaningful exchange in this time of difficult and uneasy isolation. In facing grandiose grief in a larger picture of climate crisis, my experience here similarly revealed, or rather, reminded me of this magic between both the intimate and infinite.

Noelle Herceg is an ECA artist member and MFA candidate in art at the University of Oregon in Eugene, OR.

Common Ground is a platform for a host of conversations and events alongside an exhibition with works by Eugene Contemporary Art artist members and invited artists on the topic of art and ecology.