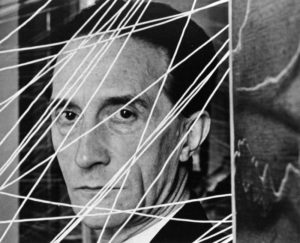

Duchamp and Dada – Q & A with Dr. Wesley Hurd

On April 25th, 2013 ECA will present “Duchamp and Dada” by Wesley Hurd, MFA, Ph.D – the first of three lectures in a series titled “3 Artists”. The following lectures in the series will focus on Andy Warhol and Joesph Beuys, who along with Duchamp comprise pivotal figures in contemporary art history. This interview was conducted by ECA Director Courtney Stubbert.

Courtney Stubbert (ECA Director): In 2012 you did a four- part lecture series for ECA called “What is Art?” It touched on the broader context of the 20th century and the forces that shape contemporary art making today as we know it. What was the motivation for focusing on Duchamp, Warhol, and Beuys specifically?

Dr. Wesley Hurd: The “What is Art?” series was my attempt to present a brief, “user-friendly” art history narrative of images that surveyed the swiftly changing, and often enigmatic, images of 20th century art—from early modernism to “high” modernism to post-modernism. But my interest in these talks was also to cover what I might call the “flow of logic” in the unfolding ideas and sensibilities of this “new” art.

I was doing my own version of answering the question, “How do we make sense of the strangeness of modern and postmodern art?” Since I am an artist, not an art historian, these talks were not “academic”, though by necessity they had to deal with some of the complex ideas behind 20th century imagery—from abstract to “conceptual” art forms and practices. My real purpose in these talks was to unpack for the non-specialist, but art-interested person, a way to understand how we got from traditional to modern to what is now most often called “contemporary” art.

I was doing my own version of answering the question, “How do we make sense of the strangeness of modern and postmodern art?” Since I am an artist, not an art historian, these talks were not “academic”, though by necessity they had to deal with some of the complex ideas behind 20th century imagery—from abstract to “conceptual” art forms and practices. My real purpose in these talks was to unpack for the non-specialist, but art-interested person, a way to understand how we got from traditional to modern to what is now most often called “contemporary” art.

In this next three talks I will go into more detail on how and why these three artists were arguably the most influential artists— Duchamp, Warhol, Joseph Beuys— in that flow of evolving 20th century art making.

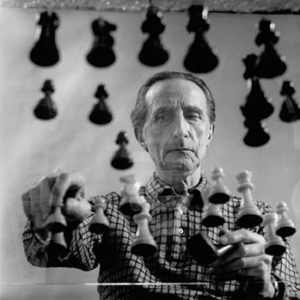

CS: We are almost 100 years from the appearance of Duchamp’s infamous “Fountain” (1917). Considering he quit making art at a certain point in favor of playing chess, what is it about Duchamp that is relevant to art making and artists today?

WH: Duchamp is now recognized as the artist who turned accepted ideas about what art is, inside out and upside down. Among his peers he stands nearly alone in creating new ideas and making art that was strange, subversive and very elusive. His art work and the ideas behind it have resulted in creating a new paradigm for thinking about art. His more famously known works—the “ready-mades” and “The Large Glass”—represent the outworking of his redefining of art. Duchamp created a new conceptual map and vocabulary leading to the new art forms and practices of the late 20th century.

All of today’s new visual art forms and strategies—performance art, installation art, multi/mixed media, site-specific, land art, and video art—all place as much, or more emphasis on “the conceptual” as on the visual. Or what Duchamp called “retinal art”. You can thank or criticize Duchamp for the often heard remark “That can’t be art!”

CS: Dada and Duchamp are usually synonymous, but Duchamp seems to exist above and beyond the reach of Dada. What’s the difference between them?

WH: For a while, Duchamp was a significant participant in the Dada art movement. Dada’s members, from Europe to New York City, displayed very diverse art but recognizable unity in their shared desire to disrupt and counter the ideals of high culture embedded in the foundations of the western civilized world. Duchamp lived and worked happily in this mode for several years.

But his distinction is found in the ideas about art that he alone generated. Put differently, he shared much with Dada’s agenda, but his work, ideas and concepts proved more radical and potent than the principles of Dada. Duchamp’s subversion of accepted ideas of art continued throughout his life, whereas the Dada movement had died out by 1923 giving much of its energy to Surrealism.

CS: Why do you think he ended up favoring Chess over art making?

CS: Why do you think he ended up favoring Chess over art making?

WH: Duchamp is famous for “giving up” or “resigning” from being an artist. Quite early in his career he stopped painting because he felt he had exhausted its possibilities for himself. When he gave up being an artist to play chess, he was quite serious. His father and family had been enthusiastic chess players. Duchamp played exceptionally well, displaying his talent in professional and amateur chess tournaments – one or two of which he won.

However, his move (pun intended) to playing chess indicated more than a simple love of the game. It was also, and simultaneously, 1) a sort of nihilistic, playful, “life-performance” that displayed his rejection of the category and importance of art, and, 2) a clear personal statement that living life with all of its complexities, simplicities and games was just as valid as what most cultured folks think of as the “high” pursuit of being an artist. His abandonment of art making—until much later in his life—for playing chess was strangely coherent with his ideas about life and art.

CS: Warhol and Duchamp famously crossed paths in the 60’s, and there is a clear connection between Warhols appropriations and Duchamp’s readymades. What about Beuys and Duchamp? What did Beuys get from him, if anything at all?

WH: Though Beuys employed art making strategies that reflected much of what Duchamp invented, he believed that art could change the world socially and spiritually. Duchamp could not have been more opposed to such perspective. Duchamp, both in personality and philosophical preference, kept himself from “using” his art in a socially or politically relevant way. He did not believe the aesthetic production of art should or could be counted on to move people toward “causes”. He lived and worked philosophically in a “zone of personal / social indifference”. In many ways Duchamp was a nihilist. Beuys, by deep contrast, was a seriously spiritual and politically driven artist, and didn’t buy into Duchamp’s aesthetic indifference.

Join us for “3 Artists – Duchamp and Dada” on April, 25th, 2013, at 7pm. Hosted at our Wave Gallery space at 547 Blair Blvd, Eugene, Oregon, 97402. Cost: $5 donation.