Critical MAS: Kathleen Caprario’s seductively beautiful painting lures into thorny landscapes

Written by Leah Wilson

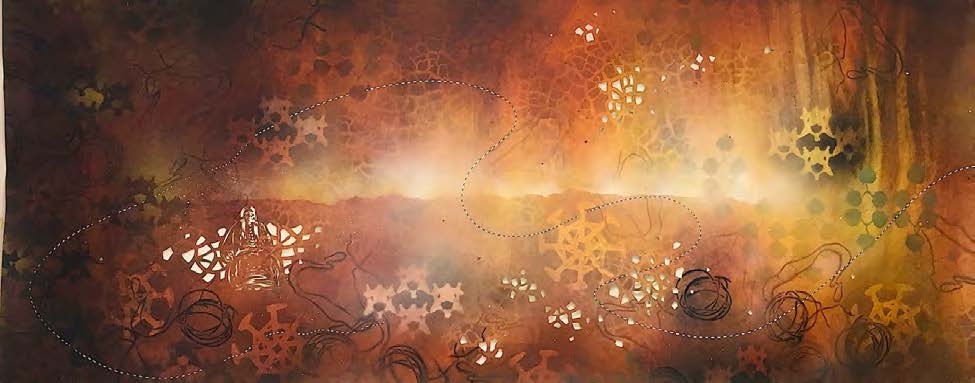

Springfield artist Kathleen Caprario’s mixed media painting at the 2019 Eugene Mayor’s Art Show is a subtle and beautiful manifestation of the examination of her position of privilege as a white woman in the United States. The large-scale, layered painting on paper does not shout its conceptual framework at the viewer, as much socially-oriented contemporary artwork does. Instead, the artist’s use of light and color draws you in gently, like a moth through an open window on a hot summer evening to your kitchen light fixtures, inviting you to enter gracefully into the thorny landscape of race and gender. A line slicing through the center of the painting, radiating white through and above it, reads as a distant ridge line of a hot landscape at sunrise, or a burning white gash cutting though a murky-patterned wallpapered wall that leads to an otherworldly portal beyond. Does the portal transport us through time as well as to a specific landscape?

Approaching for a closer look, it becomes apparent that not only does the image glow, but the entire piece is luminous with color, light, and shadow. Cutouts reveal pools of green spilling onto the gallery wall within the ambiguous landscape, and the edges burn with a rusty orange radiance. The use of chromatic light, in conjunction with pigmented color, adds to the otherworldly quality. However, the small black pushpins securing the artwork to the wall break the illusion momentarily, forcing it back into the physical reality of a painting competing for attention on gallery walls overly crowded with unrelated artwork. I would have preferred to not see the pushpins, and instead, be rewarded to find that this strange image appears to hover from the wall as if it defies not only time, but also gravity.

The repeating shapes floating in front of the landscape create a web-like pattern of tumbling wheels and imagery that resembles cut out paper chains or strange chemical bonds. I had no reference point to interpret these patterns from the imagery alone, although I assumed they have specific meanings. Later, I learned from the artist statement that the patterns are “symbols that represent the West and its resources – cattle, oil and water.” It is easy to malign industrial land use, especially regarding resources like cattle and oil that have wreaked havoc on this country’s native ecosystems. But Caprario chooses to employ the symbols as if they were banal decoration—wallpaper superimposed over the land. The history of land use in the Western United States, and the stories we weave around it, often render devastating land use legacies as ordinary, nothing that requires close attention; similar to easily overlooked wallpaper in a dentist’s office.

Looking more closely at the patterns embedded in the landscape, I finally notice a small, easily overlooked seated female figure cut out of the paper. Her image is literally removed from the landscape. Again, only later did I learn that, “[t]he cut out was taken from a 19th c. photograph. Historic photos of Native American Women are rarely named and through that lack of acknowledgement, it objectifies them…”

Caprario’s patterned imagery is multilayered and complex, which underscores the complex and multilayered history of race and gender with which she is grappling. She expects much from her audience. Caprario does not immediately reveal the gut punch embedded in her artwork. Allow yourself to be lured into the metaphorical landscape. Stay long enough for the beauty of it to begin revealing the dark undertones of our past that beckon to be acknowledged.

To learn more about the writing in the Critical MAS series, go to Critical MAS: Introduction.